Eureka City, Barberton’s forgotten wild-west gold town

At its height in the 1880s, Eureka City was a thriving mining camp of roughly 650 diggers, speculators, and adventurers, all lured by the promise of fast fortunes in gold.

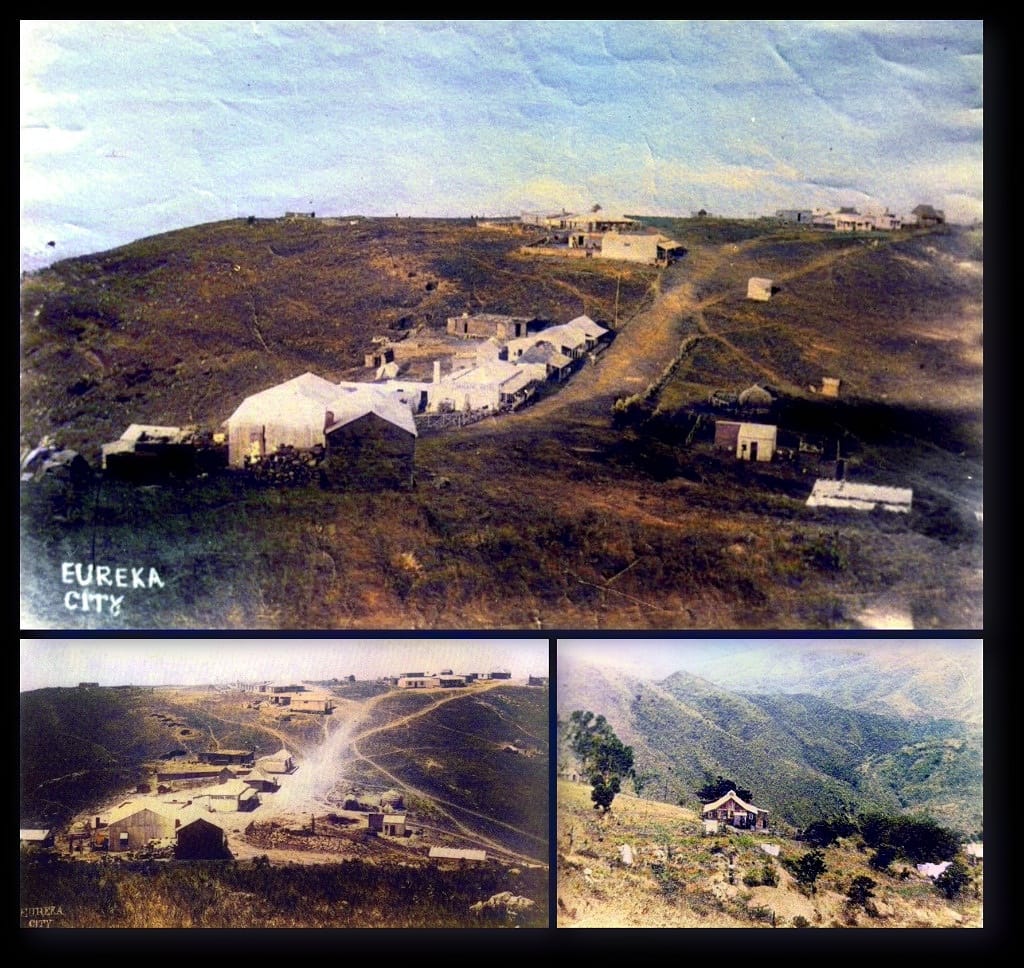

High in the rugged Makhonjwa Mountains northwest of Barberton lie the faint remains of Eureka City. A ghost town that flared to life during the gold rush and faded just as quickly.

At its height in the 1880s, Eureka City was a thriving mining camp of roughly 650 diggers, speculators, and adventurers, all lured by the promise of fast fortunes in gold. For a brief, glittering moment, it seemed destined to become one of Barberton’s great settlements. It boasted two hotels, several canteens and music halls, a bakery, a racecourse, and a host of boarding houses catering to miners who worked the rich Sheba Reef nearby.

The atmosphere was more frontier than civilized town. Old-timers called it “a bit of Barberton’s Wild West,” a place where miners celebrated paydays with horse races, gambling, and barrels of gin, and where the law often arrived long after the trouble had already passed.

The discovery of gold in the Barberton district in 1883 sparked one of the region’s earliest gold rushes. The Sheba Reef, particularly rich in ore, drew hundreds of prospectors who hacked trails up into the mountains to stake their claims. Eureka City grew around this feverish activity almost overnight.

It wasn’t a town built from bricks, but of stone, corrugated iron, timber, and tented canteens, quick to build and just as quick to vanish when the gold began to run out. Yet during its short life, Eureka City offered nearly everything a miner could desire: places to sleep, eat, drink, and gamble, and even entertainment for those with coins to spare.

Horse racing was a favorite diversion. Old accounts tell of miners thundering through the main street on horseback, racing for bragging rights and hastily collected prize money, while fellow diggers cheered and bet from the roadside.

Eureka City’s remoteness made it difficult to police. While Barberton had a magistrate and a semblance of order, Eureka was left largely to govern itself and when miners are left to write their own rules, disputes are settled with fists, pistols, or rope.

One tale that survives from this era is both disturbing and legendary. A Chinese man, accused of theft, was seized by a mob of angry diggers and hanged from a Marula tree. Before life ebbed away, a local policeman intervened, cut the rope, and whisked him into hiding. The man disappeared and was never seen again. Whether he fled the mountains or met another fate remains unknown.

Such stories remind us that Barberton’s gold rush was not only a tale of enterprise, but also of rough justice, greed, and survival at all costs.

Like many gold-rush settlements, Eureka City’s fortunes faded almost as quickly as they rose. By the late 1880s, richer finds elsewhere, and the gradual depletion of easy ore on the Sheba Reef, sent miners scattering to other camps. Buildings were dismantled or abandoned, the racecourse overgrown, and the music halls fell silent. By the 1890s, only stone walls and a few rusting relics remained where once there had been noise, dust, and gold fever.

Today, visitors to Eureka City will find crumbling foundations, scattered rocks, and weathered paths overtaken by grass. Yet, standing there, with sweeping views over the Barberton valley, it’s easy to imagine the clatter of hooves, the roar of drunken laughter, and the clinking of gold coins on a saloon counter.

Hikers and history enthusiasts can access the site through guided routes that climb into the Makhonjwa Mountains. The trip is well worth the effort: not only for its sense of adventure but for the panoramic views and the connection to a dramatic chapter of Barberton’s past.

Local guides often share anecdotes that aren’t found in the history books. Stories of diggers who struck gold only to drink it away in a week, and of others who died penniless in their tents.

Barberton is proud of its gold-rush roots, and places like Eureka City help keep that history alive. While the town itself may have vanished, its story lives on through local heritage projects, historical societies, and tourism initiatives.

The Barberton Makhonjwa Mountains, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, preserve not only some of the oldest exposed rocks on Earth but also the human stories of pioneers who risked everything for gold. Eureka City’s ruins form part of this rich cultural landscape, offering lessons in resilience, ambition, and the fleeting nature of fortune.

Preserving and sharing this history benefits more than just tourism. It gives younger generations a deeper understanding of how Barberton’s adventurous spirit was forged in hardship, opportunity, and determination.

Although not a commercial tourist stop like Pilgrim’s Rest, Eureka City can be visited on foot or by arranging excursions with local hiking groups or guides familiar with the old mining roads. The Barberton Tourism Office and heritage tour operators can provide up-to-date information for those who want to explore the site responsibly.

Sturdy walking shoes, plenty of water, and a healthy dose of curiosity are all you need. What you’ll gain in return is an unforgettable glimpse into Barberton’s past, and perhaps a renewed appreciation for the brave, reckless souls who built a gold town on a mountainside, only to see it vanish like dust in the wind.

• 𝙵𝚘𝚛 𝚜𝚝𝚘𝚛𝚢 𝚜𝚞𝚋𝚖𝚒𝚜𝚜𝚒𝚘𝚗𝚜 𝚘𝚛 𝚛𝚎𝚟𝚒𝚎𝚠𝚜, 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚝𝚊𝚌t Lynette 𝚟𝚒𝚊 𝚎𝚖𝚊𝚒𝚕 (editor@dekaapecho.co.za).

• 𝙵𝚘𝚛 𝚙𝚊𝚛𝚝𝚗𝚎𝚛𝚜𝚑𝚒𝚙𝚜, 𝚖𝚊𝚛𝚔𝚎𝚝𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚘𝚛 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚝𝚎𝚗𝚝 𝚎𝚗𝚚𝚞𝚒𝚛𝚒𝚎𝚜, 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚝𝚊𝚌𝚝 𝙰𝚗𝚌𝚑𝚎𝚗 𝚟𝚒𝚊 𝚎𝚖𝚊𝚒𝚕 (𝚊𝚗𝚌𝚑𝚎𝚗@𝚒𝚘𝚕𝚘𝚐𝚞𝚎𝚖𝚎𝚍𝚒𝚊.𝚌𝚘𝚖) 𝚘𝚛 𝚜𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚊 𝚆𝚑𝚊𝚝𝚜𝙰𝚙𝚙 𝚑𝚎𝚛𝚎.

Comments ()