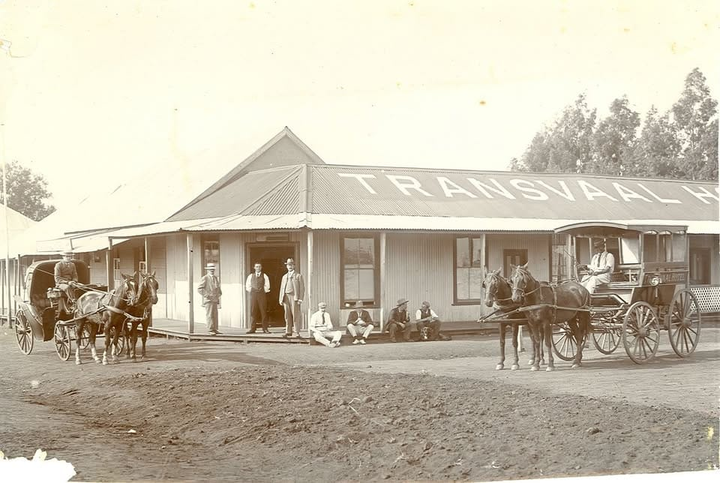

Barberton hosted Transvaal’s first stock exchange

Barberton wasn’t just a mining camp. In the 1880s it briefly hosted the Transvaal’s first stock exchange.

Barberton wasn’t just a mining camp. In the 1880s it briefly hosted the Transvaal’s first stock exchange.